Michael Molloy joined the Irish Volunteers in 1914. In 1915 when James Connolly started his newspaper The Workers’ Republic, he recruited Michael to take charge as compositor in the Printing Office that had been established in the Basement in Liberty Hall.

The existence of an illicit printing press was known to the British authorities, but they were unable to discover its exact location. On occasions the RIC had been forced out of Liberty Hall at gunpoint by Connolly himself and also by Countess Markievicz as they tried to enter via her clothing store. The material being printed under Connolly’s aegis was regarded as seditious and illegal and the RIC were keen to shut it down.

At the time the authorities in Dublin were in censorship mode having also shut down a journal called The Gael and seized all the printing machinery including type.

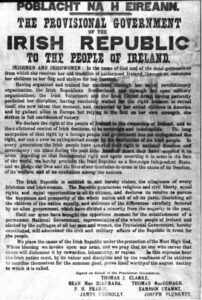

In planning the events of Easter 1916, the leaders of the Easter Rising had drafted a Proclamation that they agreed would be read from the steps of the GPO announcing the creation of the Irish Republic. The decision was taken to print numerous copies of the Proclamation for distribution across Dublin and farther afield so that the Irish people were aware of the momentous events that were underway.

On Good Friday, James Connolly instructed Michael Molloy, and his two colleagues Christopher Brady and William O’Brien to prepare for the printing of the Proclamation, which he said he needed for Easter Sunday. In briefing his men he told them it would be similar in size to an Auctioneer’s notice and would require the sort of type used in posters.

– He told them that they would print a document “that would live in history.”

In their printing works in Liberty Hall Molloy and his fellow printers did not have enough of the right type to print a Proclamation as specified by Connolly, and following his orders they visited a number of printers in Dublin to acquire suitable type, but were unable to get any. At the third printers, West’s of Capel Street they convinced the printer to lend them all of the Double Great Primer print type that he owned.

The printer concerned, a Mr Graham, was reluctant but acquiesced when told that they were taking the print whether he liked it or not.

The spoils were wheeled back to Liberty Hall in a Hand Cart. Upon learning that his men had been successful, Connolly advised them that he needed them to return to Liberty Hall at 9.00am on Easter Sunday morning to print the Proclamation. He told them that they would print a document “that would live in history.”

As anyone who studied Irish History will know, the Irish Volunteers leader Eoin MacNeill countermanded the order for the Rising on Easter Sunday, following the capture of Roger Casement in Banna Strand. All Volunteers were ordered by O’Neill to stand down.

James Connolly, Padraig Pearse and the other leaders decided to proceed with the insurrection on Easter Monday. Molloy and his fellow printers were instructed to proceed as ordered. To do so, they were handed a handwritten copy of the Proclamation. To dispel any doubts they held as to its provenance, Connolly offered to have it signed by the seven signatories to prove its veracity. As he secured the signatures of the other men, the printers got the printing type and press ready in Liberty Hall to begin their task. The printing press in their possession was a Summit Wharfedale Stop Cylinder Press.

It is interesting that Molloy for a while had in his possession what would have been the most iconic document in Irish history – a signed handwritten manuscript version of the Proclamation. He later chewed it up and swallowed it after he was captured by British Forces. He wanted to ensure it didn’t pass into enemy hands and may also have realised possession could have led to his execution.

Molloy and his comrades set to work setting the type around 11.00am on Easter Sunday. Not having enough type to complete the entire Proclamation on one sheet, and even then having to repair broken type with wax, and replaced missing letters with replacements from other typefaces, the decision was taken to set and print the document in two halves.

Molloy and his comrades set to work setting the type around 11.00am on Easter Sunday. Not having enough type to complete the entire Proclamation on one sheet, and even then having to repair broken type with wax, and replaced missing letters with replacements from other typefaces, the decision was taken to set and print the document in two halves.

With Connolly’s approval, and having printed a quantity of 1000 copies of the first half, the type was broken up and the remainder set to complete the bottom half of the Proclamation. The job was finally completed close to midnight on Easter Sunday night. Ironically had the Rising gone ahead as planned, the Proclamation in print form would not have been ready, a footnote that is rarely if ever mentioned in history.

In authentic copies that exist to this day you can see the gap between paragraphs three and four. The use of the letter ‘e’ from a different font is also clear to see in authentic copies of the original, as is the broken type in the letter ‘R’ of Irish Republic and printing of a letter ‘e’ upside down in the last paragraph. The document has other type idiosyncrasies and unusual spacing here and there. Due to the type, the printing in two halves, the idiosyncrasies of the press, many original copies differ slightly in small detail.

Given the hurried conditions, the potential for an RIC or British raid and the pressure from the leaders to get the work completed it is a remarkable feat of printing. ‘It is a wonder how we produced it at all,’ said Molloy in an interview years later.

On Easter Monday morning it was these posters that were distributed throughout Dublin, and reading from one of them, Padraig Pearse declared an Irish Republic from the steps of the GPO.

The Rising of course was met with lukewarm indifference in Dublin and it was only with the execution of the leaders, James Connolly in particular, that the public view of the Rising began to change. At that stage, many of the posters had been ripped down in anger by the citizens of Dublin who were unsympathetic to the cause.

In the aftermath of the surrender, British soldiers that stumbled upon the makeshift printing works realised that the Proclamation had been printed there because the type was still set. A number ran off ‘half copies’ made from what remained of the type set on the press as souvenirs. These comprised only the bottom half of the document.

If you come upon an original copy in your attic, or your grandparents house, you are one of the lucky ones. Despite many reprints and souvenir prints, it is estimated there are around thirty known original copies still in existence.

Footnote:

James Connolly was shot by firing squad on 12 May 1916. As he was injured the British Army Execution Party shot him seated, tied to a chair. His execution in particular and the manner in which it took place provoked outrage in Ireland and even in England and led to a sway in public opinion.

Michael Molloy fought in the Rising and was imprisoned for his part in it. He later worked as a printer for the Irish Independent and gave a witness account of the events he participating in during Easter 1916. It is held in the National Library.

Just wanted to say my grandfather was Michael Molloy.my mother was Pauline Molloy . Who married my father John Harrison .I enjoyed reading your story